Toxic Culture Is Driving the Great Resignation

More than 40% of all employees were thinking about leaving their jobs at the beginning of 2021, and as the year went on, workers quit in unprecedented numbers.1 Between April and September 2021, more than 24 million American employees left their jobs, an all-time record.2 As the Great Resignation rolls on, business leaders are struggling to make sense of the factors driving the mass exodus. More importantly, they are looking for ways to hold on to valued employees.

To better understand the sources of the Great Resignation and help leaders respond effectively, we analyzed 34 million online employee profiles to identify U.S. workers who left their employer for any reason (including quitting, retiring, or being laid off) between April and September 2021.3 The data, from Revelio Labs, where one of us (Ben) is the CEO, enabled us to estimate company-level attrition rates for the Culture 500, a sample of large, mainly for-profit companies that together employ nearly one-quarter of the private-sector workforce in the United States.4

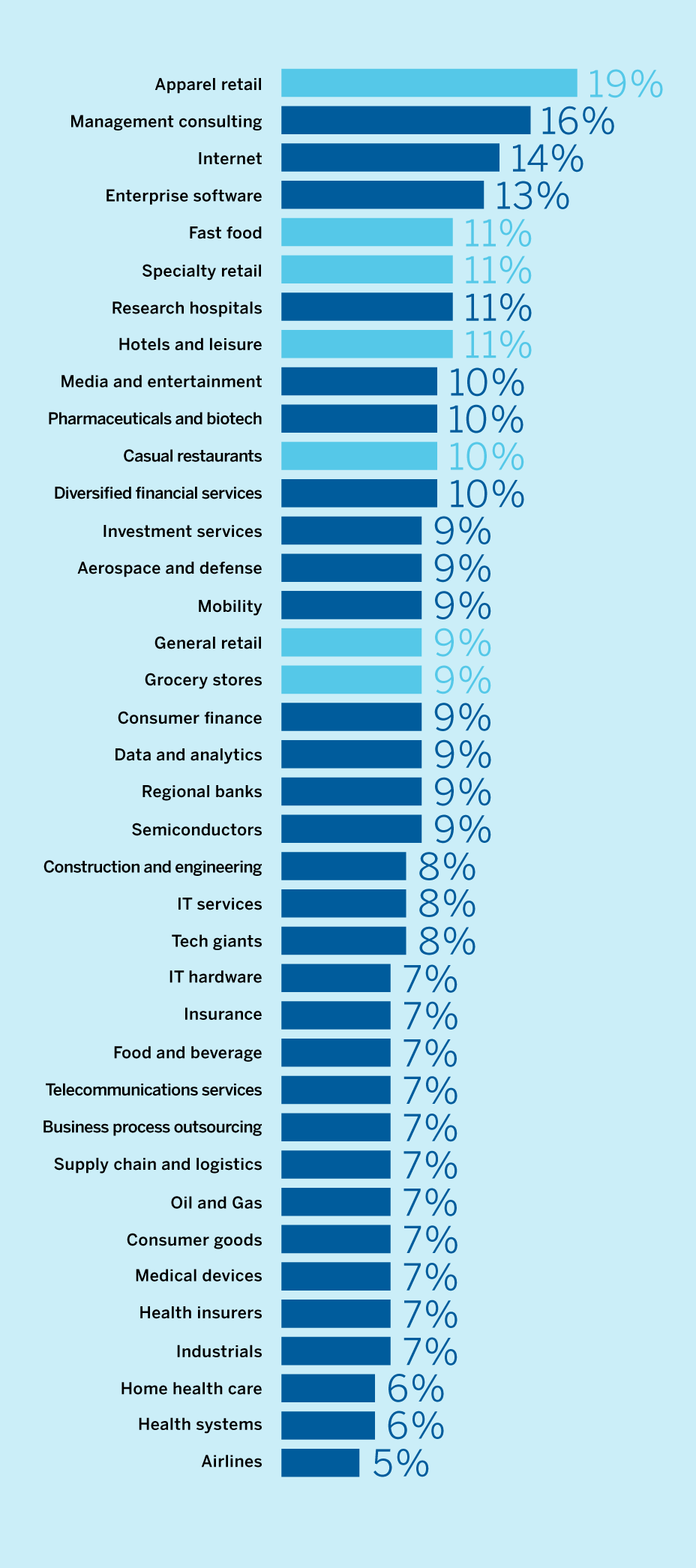

While resignation rates are high on average, they are not uniform across companies. Attrition rates for the six months we studied ranged from less than 2% to more than 30% across companies. Industry explains part of this variation. The graph below shows the estimated attrition rate for 38 industries from April through September, and the spread across industries is striking. (See “Industry Average Attrition Rate in the Great Resignation.”) Apparel retailers, on average, lost employees at three times the rate of airlines, medical device makers, and health insurers.

The Great Resignation is affecting blue-collar and white-collar sectors with equal force. Some of the hardest hit industries — apparel retail, fast food, and specialty retail — employ the highest percentage of blue-collar workers among all industries we studied. Management consulting, in contrast, had the second-highest attrition rate but also employs the largest percentage of white-collar professionals of any Culture 500 industry. Enterprise software, which also suffered high churn, employs the highest percentage of engineering and technical employees.

Industry explains some of the variation in attrition rates across companies but not all of it. Even within the same industry, we observed significant differences in attrition rates. The figure below compares competitors with high and low attrition rates within their industries. (See “How Culture 500 Company Attrition Rates Compare Within Industries.”) Workers are 3.8 times more likely to leave Tesla than Ford, for example, and more than twice as likely to quit JetBlue than Southwest Airlines.

Not surprisingly, companies with a reputation for a healthy culture, including Southwest Airlines, Johnson & Johnson, Enterprise Rent-A-Car, and LinkedIn, experienced lower-than-average turnover during the first six months of the Great Resignation. Although the sample is small, these pairs hint at another, more intriguing pattern. More-innovative companies, including SpaceX, Tesla, Nvidia, and Netflix, are experiencing higher attrition rates than their more staid competitors. The pattern is not limited to technology-intensive industries, since innovative companies like Goldman Sachs and Red Bull have suffered higher turnover as well.

To dig deeper into the drivers of intra-industry turnover, we calculated how each Culture 500 company’s attrition rate compared with the average of its industry as a whole. This measure, which we call industry-adjusted attrition, translates each company’s attrition rate into standard deviations above or below the average for its industry.5

We also analyzed the free text of more than 1.4 million Glassdoor reviews, using the Natural Employee Language Understanding platform developed by CultureX, a company two of us (Donald and Charles) cofounded. For each Culture 500 company, we measured how frequently employees mentioned 172 topics and how positively they talked about each topic. We then analyzed which topics best predicted a company’s industry-adjusted attrition rate.

Top Predictors of Employee Turnover During the Great Resignation Much of the media discussion about the Great Resignation has focused on employee dissatisfaction with wages. How frequently and positively employees mentioned compensation, however, ranks 16th among all topics in terms of predicting employee turnover. This result is consistent with a large body of evidence that pay has only a moderate impact on employee turnover.6 (Compensation can, however, be an important predictor of attrition in certain settings, such as nurses in large health care systems).

In general, corporate culture is a much more reliable predictor of industry-adjusted attrition than how employees assess their compensation. The figure below displays the five predictors of relative attrition. (See “Top Predictors of Attrition During Great Resignation.”) To give a sense of their relative importance, we’ve benchmarked each element relative to the predictive power of compensation.7 A toxic corporate culture, for example, is 10.4 times more powerful than compensation in predicting a company’s attrition rate compared with its industry.

Let’s take a closer look at each of the top five predictors of employee turnover.

Toxic corporate culture. A toxic corporate culture is by far the strongest predictor of industry-adjusted attrition and is 10 times more important than compensation in predicting turnover.

Our analysis found that the leading elements contributing to toxic cultures include failure to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion; workers feeling disrespected; and unethical behavior. In an upcoming article, we will dive deeper into each of these factors and examine different ways managers and employees can spot signals of toxic culture.8 For now, the important point is that a toxic culture is the biggest factor pushing employees out the door during the Great Resignation.

Job insecurity and reorganization. In a previous article, we reported that job insecurity and reorganizations are important predictors of how employees rate a company’s overall culture. So it’s not surprising that employment instability and restructurings influence employee turnover.9 Managers frequently resort to layoffs and reorganizations when their company’s prospects are bleak. Previous research has found that employees’ negative assessments of their company’s future outlook is a strong predictor of attrition.10 When a company is struggling, employees are more likely to jump ship in search of more job security and professional opportunities. Past layoffs, moreover, typically leave surviving employees with heavier workloads, which may increase their odds of leaving.

Another reason job insecurity could predict turnover is related to our measure of employee attrition, which incorporates job changes for all causes — including layoffs and involuntary terminations. We would expect frequent mentions of reorganizations and layoffs to predict involuntary turnover. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, however, involuntary separations have accounted for less than one-quarter of all employee exits among large companies during the Great Resignation.11 So it’s likely that poor career prospects and job insecurity contributed significantly to employees leaving on their own accord as well.

High levels of innovation. It’s not surprising that workers leave companies with toxic cultures or frequent layoffs. But it is surprising that employees are more likely to exit from innovative companies. In the Culture 500 sample, we found that the more positively employees talked about innovation at their company, the more likely they were to quit. The attrition rates of the three most innovative Culture 500 companies — Nvidia, Tesla, and SpaceX — are three standard deviations higher than those in their respective industries.

Staying at the bleeding edge of innovation typically requires employees to put in longer hours, work at a faster pace, and endure more stress than they would in a slower-moving company. The work may be exciting and satisfying but also difficult to sustain in the long term. When employees rate their company’s innovation positively, they are more likely to speak negatively about work-life balance and a manageable workload. During the Great Resignation, employees may be reconsidering the personal toll that relentless innovation takes.

Failure to recognize performance. Employees are more likely to leave companies that fail to distinguish between high performers and laggards when it comes to recognition and rewards. Companies that fail to recognize and reward strong performers have higher rates of attrition, and the same is true for employers that tolerate underperformance. The issue is not compensation below market rates, but rather recognition — both informal and financial — that is not linked to effort and results. High-performing employees are the most likely to resent a lack of recognition for their results, which means that companies may be losing some of their most productive workers during the Great Resignation.

Poor response to COVID-19. Employees who mentioned COVID-19 more frequently in their reviews or talked about their company’s response to the pandemic in negative terms were more likely to quit. The same pattern holds true when employees talk more generally about their company’s policies for protecting their health and well-being.

Short-Term Actions to Boost Retention

The powerful predictors of attrition listed above are not easy to change. A weak future outlook that spurs restructuring and layoffs may be difficult to reverse; it is too late to fix a poor response to the pandemic; and a toxic corporate culture cannot be improved overnight. Relentless innovation provides companies like Tesla or Nvidia with a competitive advantage, so they must find ways to retain employees without sacrificing their innovation edge.

Our analysis identified four actions that managers can take in the short term to reduce attrition. (See “Short-Term Steps for Companies to Increase Retention.”) As in the graph above, each bar represents the topic’s predictive power relative to compensation. This time, the topics predict a company’s ability to retain employees compared with industry peers. Providing employees with lateral career opportunities, for example, is 2.5 times more powerful as a predictor of a company’s relative retention rate compared with compensation.

Provide opportunities for lateral job moves. Not all employees want to climb the corporate ladder or take on additional work or responsibilities. Many workers simply want a change of pace or the opportunity to try something new. When employees talk positively about lateral opportunities — new jobs offering fresh challenges without a promotion — they are less likely to quit. Lateral career opportunities are 12 times more predictive of employee retention than promotions. We observed the same pattern in multinationals: The more frequently employees discussed the possibility of international postings, the more likely they were to stick with their current employer.

Sponsor corporate social events. Company-organized social events, including happy hours, team-building excursions, potluck dinners, and other activities outside the workplace are a key element of a healthy corporate culture, so it’s no surprise that they are also associated with higher rates of retention.12 Organizing fun social events is a low-cost way to reinforce corporate culture as employees return to the office, and it strengthens employees’ personal connections to their team members.

Offer remote work options. Much of the media coverage of the Great Resignation has focused on the importance of remote work in retaining employees. Unsurprisingly, when employees discussed remote work options in more positive terms, they were less likely to quit. What you might not have expected is the relatively modest impact of remote work on retention — just a bit more powerful than compensation in predicting lower attrition. Remote work options may have a modest effect on employee turnover because most companies in an industry converge on similar policies. If companies cannot differentiate themselves based on remote work options, they may need to look elsewhere — providing lateral job opportunities, for instance, or making schedules more predictable — to retain employees.

Make schedules more predictable for front-line employees. When blue-collar employees describe their schedules as predictable, they are less likely to quit. Having a predictable schedule is six times more powerful in predicting front-line employee retention than having a flexible schedule. (A predictable schedule has no predictive power for white-collar employees.)

This finding is consistent with a study of 28 Gap stores, in which employees at randomly-assigned locations received their work schedules two weeks in advance, and their managers were barred from canceling their shifts at the last minute. Employees in the control stores were subject to the usual scheduling practices.13 The stores with predictable schedules increased retention among their most experienced associates. Compared with the workers at the control stores, the employees with fixed schedules had a 7% improvement in their quality of sleep. The benefits were especially pronounced for workers with children, who reported a 15% reduction in stress.

Much of the media coverage of the Great Resignation focuses on high turnover among burned-out knowledge workers who are dissatisfied with their stagnant wages. Our findings are broadly consistent with this narrative. Industries that employ large numbers of professional and technical employees, like management consulting and enterprise software, have experienced high turnover. We found indirect evidence that burnout may contribute to higher levels of attrition among companies that excel at innovation. It’s worth noting, however, that our direct measures of burnout, workload, and work-life balance do not emerge as key predictors of industry-adjusted turnover.

The simplistic narrative of white-collar burnout misses other critical realities of the Great Resignation. Our findings reinforce recent government statistics showing that blue-collar intensive industries like retail and fast food are experiencing unprecedented levels of attrition.14

More fundamentally, we found that corporate culture is more important than burnout or compensation in predicting which companies lost employees at a higher rate than their industries as a whole. A toxic corporate culture is the single best predictor of which companies suffered from high attrition in the first six months of the Great Resignation. The failure to appreciate high performers, through formal and informal recognition, is another element of culture that predicts attrition. A failure to recognize performance is likely to drive out a company’s most productive employees. This is not to argue that compensation and burnout don’t influence attrition — of course they do. The important point is that other aspects of culture appear to matter even more.

Our research identified four steps — offering lateral career opportunities, remote work, social events, and more predictable schedules — that may boost retention in the short term. Leaders who are serious about winning the war for talent during the Great Resignation and beyond, however, must do more. They should understand and address the elements of their culture that are causing employees to disengage and leave. And above all else, they must root out issues that contribute to a toxic culture. Our next article will explore, empirically, what constitutes a toxic culture and how organizations can address this challenge.

This article first appeared in the Jan 11, 2022 issue of the MIT Sloan Management Review

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Donald Sull (@culturexinsight) is a senior lecturer at the MIT Sloan School of Management and a cofounder of CultureX. Charles Sull is a cofounder of CultureX. Ben Zweig is the CEO of Revelio Labs and an adjunct professor of economics at New York University’s Stern School of Business.

REFERENCES (14)

1. Microsoft sponsored a survey of over 30,000 employees across 31 markets in January 2021 for its Work Trend Index. See “The Next Great Disruption Is Hybrid Work — Are We Ready?” Microsoft, March 22, 2021, www.microsoft.com.

2. “Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed Dec. 6, 2021, www.bls.gov. The data represents seasonally adjusted quits for total nonfarm employers in the U.S. from April through September 2021.

3. To test the accuracy of our estimates of employee attrition, we compared them with the November U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) for total separations (including employee resignations, layoffs, and other sources of job separations) for private companies with more than 5,000 employees. The BLS total separation rate was 10.8% for April through September 2021, and our estimates were 10.1% for the same period.

4. To estimate turnover at the company level, we identified all job transitions where a user left their current employer for any reason, including quitting, retiring, or being laid off, and divided these by corporate head count. Job transitions were measured for April through September 2021 for 538 Culture 500 companies. The attrition rates are adjusted for sampling bias related to who has an online profile and for lags in when users reported transitions on their profiles. To test the robustness of our estimates of attrition, we separately estimated the hiring rate for each company for the same period. Hiring rate is defined as employees who joined the company divided by corporate head count. We would expect hiring and attrition rates to be correlated, as companies replace employees who leave. The Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.81 between the hiring and attrition rates.

5. We assigned each Culture 500 company to a primary industry and calculated how many standard deviations the focal company’s attrition rate was above or below the industry mean. We used the resulting industry-normalized attrition rate as the dependent variable in our subsequent models. To identify which factors were most important in predicting each company’s normalized attrition rate, we used an XGBoost model and calculated the SHAP (Shapley additive explanations) value for 172 topics measured by the CultureX Natural Employee Language Understanding platform. The SHAP value approach analyzes all possible combinations of features in a predictive model to estimate the marginal impact that each feature has on the outcome — in our case, which cultural elements have the biggest impact in predicting a company’s industry-normalized attrition rate. For an overview of SHAP models, see S.M. Lundberg, G. Erion, H. Chen, et al., “From Local Explanations to Global Understanding With Explainable AI for Trees,” Nature Machine Intelligence 2, no. 1 (January 2020): 56-67.

6. A.L. Rubenstein, M.B. Eberly, T.W. Lee, et al., “Surveying the Forest: A Meta-Analysis, Moderator Investigation, and Future-Oriented Discussion of the Antecedents of Voluntary Employee Turnover,” Personnel Psychology 71, no. 1 (spring 2018): 23-65; and D.G. Allen, P.C. Bryant, and J.M. Vardaman, “Retaining Talent: Replacing Misconceptions With Evidence-Based Strategies,” Academy of Management Perspectives 24, no. 2 (May 2010): 48-64.

7. Relative importance is calculated by dividing each topic’s SHAP value by the SHAP value for the compensation topic. When highly predictive features are closely related (such as job insecurity and restructuring), we report their combined predictive impact.

8. Jason Sockin finds that “respect/abuse,” a topic that overlaps with our definition of toxic culture, is the single best predictor of employee satisfaction. See J. Sockin, “Show Me the Amenity: Are Higher-Paying Firms Better All Around?” SSRN, Nov. 18, 2021, https://papers.ssrn.com.

9. D. Sull and C. Sull, “10 Things Your Corporate Culture Needs to Get Right,” MIT Sloan Management Review, Sept. 16, 2021, https://sloanreview.mit.edu.

10. B. Zweig and D. Zhao, “Looking for Greener Pastures: What Workplace Factors Drive Attrition?” PDF file (Mill Valley, California: Glassdoor, 2021), www.glassdoor.com. A recent meta-analysis also found that job insecurity was a strong predictor of voluntary employee turnover. See A.L. Rubenstein et al., “Surveying the Forest,” 23-65.

11. In the November BLS JOLTS, seasonally adjusted layoffs and discharges for all private companies with more than 5,000 employees represented 24% of total separations for April through September 2021.

12. D. Sull and C. Sull, “10 Things.”

13. J.C. Williams, S.J. Lambert, S. Kesavan, et al., “Stable Scheduling Increases Productivity and Sales: The Stable Scheduling Study,” PDF file (San Francisco: Center for WorkLife Law, 2018), https://worklifelaw.org.

14. “Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Dec. 8, 2021, www.bls.gov.

Talent Market Drivers Since the Start of COVID

LinkedIn data on what talent wants, what employers need, and what we’re learning in the Great Reshuffle

The global talent market has never changed this much, this quickly. Call it the Great Reshuffle: a time when everyone is rethinking everything.

As employees reconsider where they work and why, employers are recalibrating their talent needs and company cultures. It’s a learning process for all involved, and this report is here to help you understand the biggest changes since the pandemic began…

It’s Time For Leaders to Get Real About Hybrid

It’s time for leaders to get real about hybrid by Aaron De Smet, Bonnie Dowling, Mihir Mysore, and Angelika Reich for McKinsey.com

Employers are ready to get back to significant in-person presence. Employees aren’t. The disconnect is deeper than most employers believe, and a spike in attrition and disengagement may be imminent.

Once in a generation (if that), we have the opportunity to reimagine how we work. In the 1800s, the Industrial Revolution moved many in Europe and the United States from fields to factories. In the 1940s, World War II brought women into the workforce (if not the C-suite) at unprecedented rates. In the 1990s, the explosion of PCs and email drove a rapid increase in productivity and the speed of decision making, ushering in the digital age as we know it today. And in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic drove employees out of offices to work from home. Thanks to the development and wide distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, 2021 presents another such opportunity. The return to the workplace is a chance to create a new, more effective operating model that works for companies and people navigating a world of increasing uncertainty. There is, however, one big catch: employers must confront the broadening disconnect between how they and their employees see the future.

Employees don’t know what they want and are reevaluating their relationships with work

More than three-quarters of C-suite executives recently surveyed by McKinsey report that they expected the typical “core” employee to be back in the office three or more days a week (Exhibit 1). While they realize that the great work-from-home experiment was surprisingly effective, they also believe that it hurt organizational culture and belonging. They are hungry for employees to be back in the office and for a new normal that’s somewhat more flexible but not dramatically different from the one we left behind.

In stark contrast, nearly three-quarters of around 5,000 employees McKinsey queried globally would like to work from home for two or more days per week, and more than half want at least three days of remote work (Exhibit 2). But their message is a bit convoluted. Many employees also report that working from home through the stress of the pandemic has driven fatigue, difficulty in disconnecting from work, deterioration of their social networks, and weakening of their sense of belonging.

When employers have small-group conversations to understand such survey results in greater detail, they discover that neither they nor large swathes of their workforces really know what employees want. This isn’t surprising. Workers have been through a lot in the past year. Many experienced unprecedented uncertainty and anxiety. They saw life-expectancy rates in their communities decrease. They managed difficult personal situations, from the loss of people close to them to their own physical- and mental-health struggles. Yet the experience wasn’t all negative. Pushed to shelter at home, many rediscovered a connection to their home and family in ways that changed them. Many workers became wealthier (because of the strong global market rebound in share prices, as well as government stimulus), giving them more confidence to reaffirm their paths through life—or choose new ones.

This increase in optionality, combined with a greater disconnect between personal lives and work obligations, is driving workers to reevaluate their relationships with their employers, as well as with their work. Today, this process of reevaluation is surfacing discordant views on returning to work. Tomorrow, it may well surface reduced engagement, greater unwillingness to work longer hours, and attrition.

Employers are underestimating the disconnect and failing to realize that the ‘finish line’ is a mirage

Many employers, keen to establish some sense of normalcy quickly, are focused on answering simple logistical questions that give them a sense of control. These questions typically focus on the number of days that employees will be in the office, collaboration tools they will use, and policies on pay levels and norms for meeting behaviors. While the answers to them can help employees who are seeking a measure of pragmatism for what comes next, they are typically accompanied by a message that the “finish line” is in sight and that we will soon enter a period of normalcy that will be the standard for many years to come.

In the enthusiasm about the return from remote working, business leaders run the risk of actually increasing the disconnect between themselves and their people. The idea that we will cross a finish line and suddenly be done with all the hard stuff seems to exist only in the minds of senior leaders.

At best, the rosy messaging of a grand return to the office is falling flat. At worst, the tone deafness of the messaging may also be accelerating what’s already shaping up to be the “great attrition” of 2021 (and 2022 and even 2023). At companies across the globe, workers are leaving at much higher rates than normal. Recent surveys found that 26 percent of workers in the United States are already preparing to look for new employment opportunities and 40 percent of workers globally are considering leaving their current employers by the end of the year.

Recent surveys found that 40 percent of workers globally are considering leaving their current employers by the end of the year.

Communicating that some magical finish line is just around the corner isn’t going to eliminate the disconnect that some employees feel between themselves and their employers—it will simply make it deeper. When people with that impression get back to the office and find that they aren’t fully reenergized, that they still feel tired, and that they still carry uncertainty and unresolved grief, they will disconnect emotionally even further from their organizations and leaders. The “finish-line effect” could drive more attrition, making things even worse for companies whose leaders are raring to go. In fact, executives who don’t expect more waves of attrition may well be kidding themselves.

Instead of directing a rah-rah return to the office, leaders would be wise to focus on deeper listening and meeting their workforces where they are today. It will be important for leaders to acknowledge, for instance, that they don't have all the answers—as their companies transition to hybrid working models, they will still be trying to discover what the right longer-term working model (the one that works for most employees) will be. It will also be important for leaders to signal that they hope to make their employees partners in designing the future of how their companies work.

Companies don’t know what comes next

Some organizations and their people are beginning to exit a grand experiment in remote working. They’ve learned many things, including how to be more productive in an operating model that was jerry rigged in a rush to meet the constant challenges and uncertainty of the COVID-19 crisis. Employers couldn’t stem the human tragedy of the pandemic, of course. But many worked with their people to figure out ingenious ways to keep their companies productive while caring for their workforces.

But the lessons learned during the pandemic only go so far in helping leaders address the next great experiment: hybrid working. A hybrid model is more complicated than is a fully remote one. At scale, using it will be an unprecedented event in which all kinds of norms that have been accepted practice for decades will be put to the test. Leaders are a long way from knowing how it will work.

A hybrid model is more complicated than a fully remote one. At scale, using it will be an unprecedented event in which all kinds of norms will be put to the test.

The question of how many days in office per week are best is the most obvious one to answer, but it isn’t the only question, and it may not even be the right one to answer first. There will likely be a bevy of questions to address: What work is better done in person than virtually, and vice versa? How will meetings work best? How can influence and experience be balanced between those who work on site and those who don’t? How can you avoid a two-tier system in which people working in the office are valued and rewarded more than are those working more from home? Should teams physically gather in a single place while tackling a project, and if so, how often? Can leadership communication to off-site workers be as effective as it is to workers in the office?

Those who are no longer working remotely must accept that they are returning to the office without clear, solid answers to such questions. We’ll get there, eventually. But policies, practices, working norms, collaboration technologies, and more will need to change and evolve as we test and learn. After emerging from the pandemic, we will be just starting a new and difficult journey.

So what should employers do to reduce the disconnect as they consider the return to in-person work? We suggest three actions.

Be clear that fixing the next operating model will take years and is a separate effort from the near-term return to the office

Many employers we talk to spend far too little time acknowledging that building the muscles for a truly effective hybrid operating model could take years, not least because they are still learning what actually works in such environments. At a time when much of the workforce is experiencing significant discontent and overwhelming exhaustion, few employees see a return to an office-centric working model as a path to improvement, and given the success of remote working in the past year, employers will be asked to justify their decisions to change the arrangement. However, if leaders are willing to start from scratch, question everything, and make intentional decisions with a clear, evidence-based rationale, the current disconnect between them and their employees could serve as the creative tension point that will power a customer-focused, employee-led operating model designed for today—and tomorrow.

Consider all the research showing that building new relationships is better done in person. During the COVID-19 pandemic, 39 percent of employees struggled to maintain a strong connection with colleagues as informal social networks weakened and people leaned in heavily to the people and groups with whom they most identified.1 Anchored in facts such as that, leaders have a concrete reason for why some amount of face time is critical. That’s also one of the reasons a company should invest in figuring out how hybrid social networks work best, along with other ways to help employees establish high-quality relationships, strengthen connections, and bolster trust. By joining employees’ search for why, leaders can begin to assemble the building blocks of a shared and nimble future-oriented culture.

Don’t just repeat what the workforce says explicitly, empathize with what they are trying to convey implicitly

Many organizations today are playing back select results of employee surveys to their workforces, partly to justify their choices about a physical return to the office. This is fine, but it fails to signal that the organization understands and appreciates the altered postpandemic relationship between employees and employers. Meeting employees where they are means signaling awareness that there is a deeper undercurrent of beliefs that will take time to surface and understand, accompanied by a clear commitment that the organization will continue to listen for, process, and act on those signals.

Doing so will mean complementing traditional listening mechanisms (such as pulse checks) with true listening, as well as intentionally creating forums and space to enable sharing. Top leaders must lead by example in showing that feedback and expressions of vulnerability are welcomed. Listening tours, fireside chats, ask-me-anything sessions, reverse town halls, and the sharing of personal stories can help build a safe environment for employees to share as well.

Team leaders must also follow through with sharing, listening, and hearing the needs of their team members. Without true partnership at that level, top leaders’ talk about partnering with employees is just that—talk.

Done right, listening at the individual level is a kind of early intervention that may head off deeper morale issues down the line. As companies move from the chaos of the pandemic to the uncertainty of the return to the office, listening to employees will continue to be more critical than ever.

Be sincere about experimenting and learning from the outcomes of your experiments

Without a road map or playbook for what the next normal should look like, people must collectively adopt a test-and-learn mindset. Organizations can try out different working models and norms, physical-space layouts, and tools to create a future that balances individual productivity with innovation-driving creativity, personal flexibility with team collaboration, and the office with the home. That means experimenting and piloting as individuals, teams, business units, offices, and organizations.

For example, the design of office space plays a key role in positive collaboration and connection, but traditional offices typically dedicate more than two-thirds of their space to individual, heads-down workspaces, such as desks and cubicles. What new designs and technologies could be piloted to provide flexibility and collaboration? One top tech company is developing an array of sensors and movable walls to allow for ongoing and real-time adjustments based on employee needs and patterns of work. A global financial-services leader is trying out a fully open floor plan with “hot desks” where management will share space with workers.

Similarly, the norms surrounding meetings are ripe for refreshing. Who needs to attend which meetings, for how long, and in what format? How can meetings be redesigned in a way that maximizes efficiency, accelerates effective decision making, and builds connectivity and social cohesion? The answers aren’t clear yet, but companies will figure them out by trial and error—by testing and learning.

Letting experiments play out will be a challenge for many leaders. As we mentioned previously, the uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic froze some leaders as it took away their sense of control. Embracing a test-and-learn culture will entail a real mindset shift for some leaders. They will need to get comfortable with the fact that a clear solution may not be immediately apparent—the big answers may not emerge for years. And they will have to help their employees adapt by providing a set of guiding principles and criteria for evaluating solutions and ideas. (For more on what leaders can do, see “Return as a muscle: How lessons from COVID-19 can shape a robust operating model for hybrid and beyond.”)

Embracing a test-and-learn culture will entail a real mindset shift for some leaders. The big answers may not emerge for years.

Denying the disconnect is no strategy at all

It would be nice if employees were jumping for joy at the prospect of a full return to the office. And it would be nice if the future turns out to be as glorious and stable as we sometimes imagine the past to have been. But those are fantasies built on nostalgia. They are anything but a solid foundation for building a future-ready company.

Right now, a lot of wishful thinking is guiding the return from remote working. With notable and heartbreaking exceptions, many leaders were insulated from the COVID-19 pandemic. They think it’s both easy and desirable for companies to move on quickly. But their people aren’t begging to disagree. They are voting with their feet.

If leaders don’t accept the fact that they don’t know the shape of the future of hybrid working, their talent will keep walking out the door. But leaders can make a choice. They can continue to believe that they will deliver in the future because they have always delivered in the past. Or they can embrace this singular opportunity for change and work with their people—closely and transparently, with curiosity, respect, and a willingness to learn together instead of mandating—to discover a new and better way to work.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Aaron De Smet is a senior partner in McKinsey’s New Jersey office, Bonnie Dowling is an associate partner in the Denver office, Mihir Mysore is a partner in the Houston office, and Angelika Reich is a partner in the Vienna office. This article was edited by Rick Tetzeli, an executive editor in the New York office.

It’s Time to Re-Onboard Everyone

It’s Time to Re-Onboard Everyone by Liz Fosslien for the Harvard Business Review, August 16, 2021

Summary. High turnover, the shift to hybrid work, and continued uncertainty about the future mean that your entire workforce may be feeling unmoored. These upheavals mean that even long-time employees — who have spent years building their reputations within an organization — may now feel they’re starting from scratch. That has enormous implications for performance, innovation, and well-being. By seizing this fall as a moment to re-onboard everyone, managers can boost team cohesion, performance, and well-being. The author presents five steps managers should take.

“I’m the most tenured person on my team,” my friend Joyce, a senior marketing manager, told me. “But I feel like a new hire.”

Despite having worked at her company for four years, a slew of recent changes had left Joyce feeling unmoored. After her manager quit in June, Joyce worked in a state of limbo for a month until she got a new boss. She started going back to the office two days a week, but soon stopped due to concerns about the Delta variant. Three of her teammates left and were replaced by four new hires.

“I barely know anyone on my team,” Joyce continued. “I can dig up documents really easily, but other than that, I might as well have joined yesterday.”

Joyce isn’t alone in feeling new to a company she’s worked at for years. As an expert on emotions at work and the head of content at Humu, a company focused on workplace behavioral change, I regularly help leaders, managers, and teams establish better ways of working. In the data and in conversations, I’ve seen two forces that are destabilizing employees: unprecedented turnover and uncertainty. The number of people switching jobs has skyrocketed to historical highs in what experts are calling “The Great Resignation.” At the same time, teams are starting to transition to hybrid work.

These upheavals mean that even long-time employees — who have spent years building their reputations within an organization — may now feel they’re starting from scratch. That has enormous implications for performance, innovation, and well-being. When we start working in a new environment or with new colleagues, we tend to feel insecure because we haven’t had a chance to prove ourselves yet. Our self-doubt makes us less likely to suggest out-of-the-box ideas, ask questions, or take needed breaks.

Great onboarding helps individuals regain their confidence and cuts down the time it takes for them to get up and running. But new hires aren’t the only people who could benefit from this type of structured support. Right now, everyone at your company needs some form of onboarding.

If you’re a leader, you can’t sit back and hope your employees will successfully navigate so much turbulence. Hope is a terrible strategy. Instead, take advantage of the fact that August tends to be a slower month at work and prepare managers now for team-wide onboarding in the fall. Here are five steps you should encourage managers to take this fall.

Kick off with connection.

When I asked Joyce what her manager had done to bring her team together, she shook her head. “Not much.”

It’s no wonder that Joyce felt disconnected at work. During periods of high turnover, you need to be especially intentional about creating opportunities for employees to get to know each other.

To set your team up for success, invest in emotional connection as soon as possible and as often as possible. Schedule random, 30-minute 1:1s between members and kick meetings off with a lighthearted prompt. (A personal favorite: “What food is underrated?”) Rituals are also a great way to create space for people to open up. Try “High, Low, Ha,” where each person shares one highlight from their week, one low point, and one thing that made them laugh.

Welcome unique contributions.

One of the first messages your reports should hear is that they will be valued for everything that sets them apart. In an onboarding experiment, researchers randomly assigned new hires to one of three different welcome sessions. The first prompted people to reflect on how their unique perspectives could help them succeed in their new roles, another asked them to think about why they were proud to join the company, and the third focused on skills training. After six months, employees in the first group were less likely to have quit and delivered higher customer satisfaction scores.

In 1:1s, ask each person to reflect on what they’re good at and how they can apply those skills to their current role. Based on these conversations, assign initial tasks that let individuals showcase their abilities. In team meetings, explicitly recognize novel suggestions. Try something like, “I hadn’t thought of it that way, thanks for pointing that out.”

Help people learn who knows what.

The most effective teams have a high level of “shared knowledge,” or a collective understanding of individual expertise, who’s responsible for what, and how everyone works together to get things done. To build shared knowledge, create early opportunities for team members to collaborate and discover each other’s unique talents. You can also start an email thread or channel where team members can post a problem for others who may have relevant experience to share their insights.

One manager I spoke with ran a three-hour sprint in which she asked her newly formed team to redesign a sales pitch deck. Afterwards, she facilitated a debrief in which the group discussed each person’s unique contributions. The exercise energized the team — and helped them get a better sense of everyone’s unique talents.

Rally everyone around a three-month mission.

Quick wins boost motivation and confidence. To empower your team to accomplish shared victories early on, unite the group around an ambitious but achievable short-term goal. Alex, an engineering manager, set a three-month mission for his team to launch a new product feature customers had been asking about for years. Having a specific, impactful goal made it easier for the group to establish clear roles and processes. Alex’s team created 30-, 60-, and 90-day plans and, at the end of every week, met to celebrate their shared progress and shout out each other’s individual achievements.

Set clear cultural expectations.

When you’re new, seemingly small uncertainties (“Can I turn my video off during longer calls?”) can become a big source of stress. To combat these anxieties, schedule time for your team to agree on cultural and emotional norms. Science shows that setting clear expectations up front can have a powerful influence on employee performance. Here are a few prompts to get you started:

How can we ensure teammates who aren’t in the office still have a voice?

How will we track progress and update each other throughout the week?

How do we each prefer to receive feedback?

What guidelines should we set for meetings?

What is it “okay” to do? (e.g., take breaks or ask questions)

Make sure to write your answers down, and save them where they’re easily accessible to everyone.

Reinforce healthy, productive norms with recognition.

Showcasing stellar work or giving kudos for supportive behaviors is one of the fastest ways to boost motivation, create a clearer picture of what is valued within your team, and positively reinforce healthy norms. Consider celebrating the efforts of a small group of people, rather than just one person or everyone. In a field experiment, researchers split employees into groups of eight, then randomly sent either the top performer, the top three performers, or everyone in the group a thank-you card for their efforts. Recognizing the top three performers in a group led to the strongest overall performance increase.

Finally, create opportunities for peers to recognize each other, too. Research shows that getting a compliment from a colleague can make new hires feel connected to the organization even faster than receiving praise from a manager. At Humu, we created a Slack channel called #cheersforpeers. Every month, anyone who has been mentioned in the channel or who recognized someone else is eligible for a raffle prize.

High turnover, the shift to hybrid work, and continued uncertainty about the future mean that your entire workforce may be feeling unmoored. By seizing this fall as a moment to re-onboard everyone, managers can boost team cohesion, performance, and well-being.

How to Reopen Offices Safely

Flush the taps, focus on indoor air quality and consider getting creative about staff schedules.

By Emily Anthes for The New York Times

For the last 15 months, many American offices sat essentially empty. Conference rooms and cubicles went unused, elevators uncalled, files untouched. Whiteboards became time capsules. Succulents had to fend for themselves.

But over the coming weeks, many of these workplaces will creak slowly back to life. By September, roughly half of Manhattan’s one million office workers are likely to return to their desks, at least part time, according to a recent survey by the Partnership for New York City.

Although the risk of contracting Covid-19 has fallen significantly in the United States — especially for those who are fully vaccinated — it has not disappeared entirely, and many workers remain nervous about returning to their desks. (Many others, of course, never had the luxury of working remotely in the first place.)

“If you’re still feeling uncomfortable or anxious, that’s totally understandable,” said Joseph Allen, an expert on healthy buildings who teaches at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “This pandemic has affected all of us in profound ways, and people are going to be ready to re-enter life again or re-enter interacting with people at different times.”

But scientists have learned a lot about the virus over the past year, and there are some clear, evidence-based steps that employers can take to protect their workers — and that workers can take to protect themselves. Some of these strategies are likely to pay dividends that outlast the current crisis.

“I think it’s important for us as a community, but also individual employers, to think about these questions in relation to not just this week and this month,” said Alex Huffman, an aerosol scientist at the University of Denver. “How do we make decisions now that benefit the safety and health of our work spaces well into the future?”

Address the risks of closures

Although Covid-19 is the headline health concern, long-term building closures can present risks of their own. Plumbing systems that sit unused, for instance, can be colonized by Legionella pneumophila, bacteria that can cause a type of pneumonia known as Legionnaires’ disease.

“Long periods with stagnant, lukewarm water in pipes — the exact conditions in many under-occupied buildings right now — create ideal conditions for growth of Legionella,” Dr. Allen said.

Some schools have already reported finding the bacteria in their water. In buildings with lead pipes or fixtures, high levels of the toxic metal can also accumulate in stagnant water. Employers can reduce both risks by thoroughly flushing their taps, or turning on the water and letting it run, before reopening.

“We know that flushing water during periods of inactivity usually reduces lead levels and also potentially bacteria that may form,” said Jennifer Hoponick Redmon, a senior environmental health scientist at RTI International, a nonprofit research organization based in North Carolina. She added: “A general rule of thumb is 15 minutes to one hour of flushing for long-term closures, such as for Covid-19.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also recommends that companies check for mold growth and pest infestations before reopening.

Upgrade ventilation and filtration

“These types of portable units can do a great job of taking particles out of the room,” Dr. Huffman said. “And the next level is even a desktop level HEPA filter, where you have a really small unit that provides clean air into your direct breathing zone.”

These personal units may be particularly helpful in poorly ventilated offices, although experts stressed that employers, not employees, should bear the burden of improving indoor air quality.

Be wary of chemical disinfection

While ventilation and filtration are crucial, employers and building managers should stay away from foggers, fumigators, ionizers, ozone generators or other “air cleaning” devices that promise to neutralize the coronavirus by adding chemical disinfectants to the air. “These are all really terrible ideas of things to do to indoor air,” said Delphine Farmer, an atmospheric chemist at Colorado State University.

The compounds that these products emit — which may include hydrogen peroxide, bleach-like solutions or ozone — can be toxic, inflaming the lungs, causing asthma attacks and leading to other kinds of respiratory or cardiovascular problems. And there is not rigorous, real-world evidence that these devices actually reduce disease transmission, Dr. Farmer said.

“A lot of employers are now — and school districts and building managers are now — thinking that they have solved the problem by using those devices,” Dr. Farmer said. “So then they are not increasing ventilation rates or adding other filters. And so that means that people think that they’re safer than they actually are.”

Surfaces pose minimal risk for coronavirus transmission, and disinfectants needlessly applied to them can also wind up in the air and can be toxic when inhaled. So in most ordinary workplaces, wiping down your desk with bleach is likely to do more harm than good, Dr. Farmer said. (Some specific workplaces — such as hospitals, laboratories or industrial kitchens — may still require disinfection, experts noted.)

Nor is there any particular need for special antimicrobial wipes or cleansers, which may fuel the emergence of antibiotic resistant bacteria and wipe out communities of benign or beneficial microbes. “As tempting as it may be to try to sterilize everything, it’s never going to happen, and there may be some real serious consequences,” said Erica Hartmann, an environmental microbiologist at Northwestern University.

Don’t depend on desk shields

In the early months of the pandemic, plastic barriers sprang up in schools, stores, restaurants, offices and other shared spaces. “They can be great to stop the bigger droplets — really they’re big sneeze guards,” Dr. Huffman said.

But the smallest, lightest particles can simply float over and around them. These barriers “may not provide enough benefit to justify their costs,” said Martin Bazant, a chemical engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. They may even raise the risk of disease transmission, by encouraging riskier behavior or impeding air flow.

There are some environments in which these kinds of barriers may still make sense. “It can be a really good idea for people who would otherwise have very close face-to-face contact, like grocery store workers at cash registers,” Dr. Farmer said. “But past that, in offices where you’re sitting for a lengthy period of time, there is no benefit to putting yourself in a plexiglass cage.”

Carefully consider staffing plans

Social distancing may still have some benefits; if an employee is exhaling infectious virus, people sitting directly in that person’s breathing zone will quite likely be exposed to the highest doses. “If you were sitting at a shared table space, two feet away from someone, then there could be some potential value to moving away a little bit further,” Dr. Huffman said.

But aerosols can stay aloft for hours and travel far beyond six feet, so moving desks farther apart is likely to have diminishing returns. “Strict distancing orders, such as the six-foot rule, do little to protect against long-range airborne transmission,” Dr. Bazant said, “and may provide a false sense of security in poorly ventilated spaces.”

In offices in which most people are vaccinated and local case rates are low, the benefits of distancing are probably minimal, scientists said. Higher-risk workplaces may want to consider de-densification, or reducing the number of people — any one of whom might be infectious — who are present at the same time. “That, to me, has been the biggest benefit of this social distancing indoors,” Dr. Farmer said. “It’s just having fewer potential sources of SARS-CoV-2 in a room.”

Companies could allow a subset of employees to work at home indefinitely or on alternating days or weeks. They could also consider “cohorting,” or creating separate teams of workers that do not have in-person interactions with those who are not on their team.

Creating these kinds of cohorts could also make it easier to respond if someone does contract the virus, allowing the affected team to quarantine without having to shut down an entire workplace. “When we think about reopening, we need to think about what do we do when, inevitably, we see a case?” said Justin Lessler, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University. “There are creative ways to lessen the impact.”

Go back to basics

Regular hand-washing, which can reduce the spread of all kinds of pathogens, is always a good idea. “The messaging at the beginning of the pandemic about washing your hands and washing your hands for at least 20 seconds — that is totally valid and still really important,” Dr. Hartmann said.

And when your office itself needs cleaning, a mild detergent will generally do the trick, she added: “Soap and water is great.”

Masks, too, remain effective. “If you’re someone who’s vaccinated and still feeling anxious about going back to work, the best thing to do is continue to wear a mask for the first couple of weeks until you feel more comfortable,” Dr. Allen said.

Scientists recommended that unvaccinated workers continue to wear masks in the office. But for those who are eligible, the most effective risk reduction strategy is obvious, Dr. Allen said: “The No. 1 thing is to get vaccinated.”

A version of this article appears in print on June 13, 2021, Section A, Page 16 of The New York Times

Covid-19 has forced a radical shift in working habits

…Mostly for the better

Self-styled visionaries and people particularly fond of their pyjamas have for decades been arguing that a lot of work done in large shared offices could better be done at home. With covid-19 their ideas were put to the test in a huge if not randomized trial. The preliminary results are now in: yes, a lot of work can be done at home; and what is more, many people seem to prefer doing it there.

This does not, in itself, mean the end of the non-home office. It does mean that there is a live debate to be had. Some companies appear relaxed about a domestic shift. On August 28th Pinterest, a social-media firm, paid $90m to end a new lease obligation on office space near its headquarters in San Francisco to create a “more distributed workforce”. Others seem to be against it. Also that month, Facebook signed a new lease on a big office in Manhattan. Bloomberg is reportedly offering a stipend of up to £55 ($75) a day to get its workers back to its building in London. Governments, on which some of the burden will fall if the pandemic persists, are taking a similar tack, encouraging people “back to work”—by which they mean “back to the office”.

They face a difficult task. For working from home seems to have suited many white-collar employees. As lockdowns have eased, people have gone out into the world once more: retail spending has jumped across the rich world while restaurant reservations have sharply risen. Yet many continue to shun the office, even as schools reopen and thus make it a more feasible option for working parents. The latest data suggest that only 50% of people in five big European countries spend every work-day in the office (see chart 1). A quarter remain at home full-time.

This may be due to the residual fear of covid-19 and the inconvenience of reduced-capacity offices. Until social-distancing guidance ends, offices cannot work at full steam. The average office can work with 25-60% of its staff while maintaining a two-meter (six-foot) distance between workers. Offices which span more than five floors rely on lifts; the queues for access, when only two people are allowed inside one, can stretch around the block.

Some offices are trying to make themselves safer places to work. The managers of a new skyscraper in London, 22 Bishopsgate, have switched off its recirculated air-conditioning. Others have installed hand-sanitizing stations and put up plastic barriers. But even if offices are safer, it can still be hard to get there. Many employees do not want to or are discouraged from using public transport—and one-quarter of commuters in New York City live more than 15 miles (24km) from the office, too far to walk or cycle.

However it also appears to be the case that working from home can make people happier. A paper published in 2017 in the American Economic Review found that workers were willing to accept an 8% pay cut to work from home, suggesting it gives them non-monetary benefits. Average meeting lengths appear to decline (see chart 2). And people commute less, or not at all. That is great for wellbeing. A study from 2004 by Daniel Kahneman of Princeton University and colleagues found that commuting was among the least enjoyable activities that people regularly did. Britain’s Office for National Statistics has found that “commuters have lower life satisfaction...lower levels of happiness and higher anxiety on average than non-commuters” (see article).

The working-from-home happiness boost could, in turn, make workers more productive. In most countries the average worker reports that, under lockdown, she got more done than she would have in the office. In the current circumstances, however, it is hard to be sure whether home-working or office-working is more efficient. Many people, particularly women, have had to work while caring for children who would normally be in school. That might make it seem as though working from home was less productive than it could theoretically be (ie, when the kids were in school).

Tumble outta bed into the kitchen

But there are lockdown-specific effects which create the opposite bias, making work-from-home seem artificially productive. During lockdown workers may have upped their game for fear of being let go by their company—evidence from America suggests that more than half of workers are worried about losing their job due to the outbreak. A separate problem is that most studies under lockdown have relied on workers to self-report their productivity, and the data generated in this way tend not to be very reliable.

Research published before the pandemic provides a clearer picture. A study in 2015 by Nicholas Bloom of Stanford University and his colleagues looked at Chinese call-center workers. They found that those who worked from home were more productive (they processed more calls). One-third of the increase was due to having a quieter environment. The rest was due to people working more hours. Sick days for employees plummeted. Another study, looking at workers at America’s Patent and Trademark Office, found similar results. A study in 2007 from America’s Bureau of Labor Statistics found that home-workers are paid a tad more than equivalent office workers, suggesting higher productivity.

The experience of lockdown has simply accelerated pre-existing trends, thinks Harry Badham, the developer of 22 Bishopsgate. That may be an understatement. Although the share of people regularly working from home was rising before the pandemic, absolute numbers remained small (see chart 3). According to one view, the fact that office-working was so dominant until recently reveals that it must be more efficient than home-based work both for firms and for workers. By this logic the success of a country’s emergence from lockdown can be measured by how many people are back at their desks.

But there is another interpretation. This says that home-working is actually more efficient than office-work, and that the glory days of the office are gone. The office, after all, came into being when the world of work involved processing lots of paper. The fact that it remained so dominant for so long may instead reflect a market failure. Before covid-19 the world may have been stuck in a “bad equilibrium” in which home-work was less prevalent than it should have been. The pandemic represents an enormous shock which is putting the world into a new, better equilibrium.

Brent Neiman of the University of Chicago suggests three factors which prevented the growth of home-working before now. The first relates to information. Bosses simply did not know whether clustering in an office was essential or not. The past six months have let them find out. The second relates to co-ordination: it may have been difficult for a single firm unilaterally to move to home-working, perhaps because its suppliers or clients would have found it strange. The pandemic, however, forced all firms who could do so to shift to home-working all at once. Amid this mass migration, people were less likely to look askance at companies which did so.

The third factor is to do with investment. The large fixed costs associated with moving from office- to home-based work may have dissuaded firms from trying it out. Evidence from surveys suggests that firms have in recent months spent big on equipment such as laptops to enable staff to work from home; this is one reason why global trade has held up better than expected since the pandemic began (see article). Such investments are made at the household level too. In many rich countries the market for single-family houses is stronger than for apartments. This suggests that people are looking for extra space, possibly for a dedicated home office.

Pour yourself a cup of ambition

The extent to which home-working remains popular long after the pandemic has passed will depend on a bargain between companies and workers. But it will also depend on whether companies embrace or reject the controversial theory that working from an office might actually impede productivity. Since the 1970s researchers who have studied physical proximity (ie, the distance employees need to travel to engage in a face-to-face interaction) have disagreed on the question of whether it facilitates or inhibits collaboration. The argument largely centers on the extent to which the bringing-together of people under one roof promotes behavior conducive to new ideas, or whether doing so promotes idle chatter.

Such uncertainty is exemplified by a study in 2017 by Matthew Claudel of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and his colleagues. Their study looked at papers and patents produced by MIT researchers and the geographical distribution of those researchers. In doing so, they found a positive relationship between proximity and collaboration. But when they looked at the buildings of MIT, they found little statistical evidence for the hypothesis that “centrally positioned, densely populated and multi-disciplinary spaces would be active hotspots of collaboration”. In other words, proximity can help people come up with new ideas, but they do not necessarily need to be in an office to do so.

However, not everything about working from home is pleasurable. In July a study from economists at Harvard, Stanford and New York University found that the average workday under lockdown was nearly 50 minutes longer than it was before, and that people became more likely to send emails after work hours. There is also wide variation between workers in how much they enjoy working from home. Leesman, a workforce consultancy, has surveyed the experience of more than 100,000 white-collar workers across the rich world during the pandemic. It finds that satisfaction with working from home varies according to whether that person has dedicated office and desk space or not.

The tide’s turned and rolling your way

And not everyone has the ability to work from home, even if they want to. Research published in April by Mr. Neiman and Jonathan Dingel, both of the University of Chicago, found that across rich countries about 40% of the workforce were in occupations that could plausibly be completed from their kitchen tables. Evidence of actual working arrangements during the pandemic backs up those speculations. A paper from Erik Brynjolfsson of Stanford University and colleagues, looking at American data, suggests that of those employed before the pandemic began, about half were working from home in May.

Indeed, it is uncertain whether the benefits of working from home can last for a sustained period of time. Mr. Bloom’s co-written study on Chinese call-center workers is one of the few to assess the impact of working from home over many months. He and his colleagues found that, eventually, many people were desperate to get back to the office, if only every now and then, in part because they were lonely. Some companies which have tried large-scale remote working in the past have ultimately abandoned it, including Yahoo, a technology firm, in 2013. “Some of the best decisions and insights come from hallway and cafeteria discussions, meeting new people, and impromptu team meetings,” a leaked internal memo read that year.

The challenge for bosses, then, is to find ways of preserving and boosting employee happiness and innovation, even as home-working becomes more common. One solution is to get everyone into the office a few days a month. An approach whereby workers dedicate a chunk of time to developing new ideas with colleagues may actually be more productive than before.

A study from Christoph Riedl of Northeastern University and Anita Williams Woolley of Carnegie Mellon University, published in 2017, suggested that “bursty” communication, where people exchange ideas rapidly for a short period of time, led to better performance than constant, but less focused, communication. Not much evidence exists that serendipity is useful for innovation, even though it is accepted by many as a self-evident truth. “A lot of people made a lot of money selling this watercooler idea,” says Mr Claudel of MIT, referring to the growth in recent decades of open-plan offices, co-working spaces and trendy “innovation districts”.

Coming into the office now and then is not the only way of generating bursty communication. The same can be achieved, say, with corporate retreats and get-togethers. Gitlab, a software company, has been “all-remote” since it was founded in 2014. With no offices, it gathers together its 1,300 “team members”, who live in 65 different countries, at least once a year for get-togethers and team bonding.

Similarly, companies such as Teemly, Sococo and Pragli offer “virtual offices”, making it easier to communicate with colleagues, rather than going through the rigmarole of scheduling a video call. Using video messaging from Loom, a worker can record her screen, voice and face and instantly share it with colleagues—more useful than a conventional video call, as the video can be sped up or rewound. Gitlab’s workers follow a “nonlinear” workday—interrupting work with bouts of leisure. Rather than talk to their colleagues over live video calls they engage in “asynchronous communication”, which is another way of saying they send their co-workers pre-recorded video messages.

More frequent working from home will also demand the use of new hardware, and the withering away of other sorts. At present, many companies host large data-centers, but these have proved less efficient as more people work from home. Goldman Sachs reckons that investment in traditional data infrastructure will fall by 3% a year in 2019-25. In its place, companies are likely to spend more on technology which allows workers to replicate the experience of being in the same physical space as someone else (higher-quality cameras and microphones, for instance). The more utopian technology analysts reckon that within five years, people will be able to put on a vr headset and immerse themselves in a virtual office—bad strip-lighting, and all.

There’s a better life

All this has wide-ranging implications for public policy. At present it is impossible to know whether home-workers will find it easier or harder to bargain with their employer for pay rises and improvements in conditions, though the idea of asking for a raise through a video chat is hardly an appealing one. Employers may also find it easier to fire remote workers than if they had to do it face-to-face. If so, then calls may grow for governments to give home-workers greater protections.

Another problem relates to employment law, argues Jeremias Adams-Prassl of Oxford University. Just as the rise of the gig economy has prompted questions and court cases about what it means to be an employee or self-employed, the increased popularity of home-working puts pressure on laws which were constructed around the assumption that people would be toiling away in an office. No one has yet thought through how firms should go about monitoring contractual working time in a world where nobody physically clocks in, nor about the extent to which firms may surveil workers at home.

Battles over employers’ responsibilities to their home-workers surely cannot be far away. Should a business pay for a worker’s internet connection or their heating in the dead of winter? Grappling with such questions will not be easy. But governments and firms must seize the moment. The pandemic, for all its ill effects, offers a rare opportunity to rewire the world of work. ■

This article originally appeared in The Economist Sep 12th 2020 edition in the Briefing section of the print edition under the headline "What a way to make a living”

REMOTE WORK ISN’T WORKING? MAYBE YOUR COMPANY IS DOING IT WRONG

Experts have tips on the office routines that need to change when everyone’s working from home. Meetings, for one.

Credit...Christie Hemm Klok for The New York Times

As the pandemic stretches on, some companies are souring on remote work. Maybe that’s because they’re not doing it right.

White-collar offices that have carried over the same conventions from the physical office have realized they don’t work well, executives and researchers say.

Companies that have changed the ways they work have had more success — and in some cases, discovered new routines that they want to continue when they return to offices. These companies have a few things in common:

They have fewer meetings that are long or large or back-to-back. They designate meeting-free time for focused work; offer flexible work hours; and find ways for colleagues to socialize when they’re not seeing one another in person.

“There’s a natural pull, even in these times, not to figure out how to operate in this new world but how to replicate the old world in the new conditions,” said Leslie Perlow, a professor of leadership at Harvard Business School. “The longer this goes on, my optimism increases because I think people are being forced to figure out innovative ways.”

In a sense, remote work during a pandemic is not actual remote work. It’s made much harder by the circumstances of the crisis, including the lack of child care, anxiety about getting sick or losing a job and the inability to work in person even if it’s desirable.

Still, employees are generally very satisfied with how it’s going. In surveys, most say that even when it’s safe for offices to reopen, they want to return only part of the time and continue working at home several days a week. That means it’s incumbent on employers to figure out how to do it well, said La’Kita Williams, founder of CoCreate Work, an executive coaching and consulting firm.

“Some bigger companies who started remote work said it failed, but one of the reasons it failed is they didn’t build the type of culture that successfully supported it,” she said.

At Microsoft, teams quickly realized that large meetings of an hour or more with vague agendas worked even less well online than in person. Back-to-back meetings were problematic, too — in offices, people rely on breaks walking from one meeting to the next to use the restroom, eat a snack or check their phones.

One 400-person team working on business software at Microsoft has seen an 11 percent decrease in hour-plus meetings and a 22 percent increase in 30-minute meetings. One-on-one meetings have increased 18 percent, according to Emma Williams, Microsoft’s corporate vice president for modern workplace transformations.

Some colleagues have also started social video meetings, like logging on while eating lunch to chat. Fridays have been designated no-meeting days, for people to focus on a project or recharge.

Another challenge Microsoft discovered: When there’s no office to leave, the lines between work and life blur. The team saw a 52 percent increase in online chats between 6 p.m. and 10 p.m.

For some people, shifting hours is helpful, because they can take time during the day for things like exercise or child care. But managers also wanted to encourage work-life boundaries. One solution was to use a tool that allows people to write messages to colleagues that aren’t sent until the next workday. Another was more one-on-one meetings between managers and employees — people who had those got their work done more quickly, probably because they were clearer on their priorities, Ms. Williams said.

Companies much smaller than Microsoft — like the Key PR, a public relations firm in San Francisco with 16 employees — have landed on similar strategies. Because its work is in client services and tied to the news, the Key PR can easily fall into a round-the-clock schedule, said Martha Shaughnessy, its founder, especially when work and home are the same place.

At first they tried letting people pick their hours, allowing afternoons or entire days off, but found it was too hard to collaborate. Now, they’re restricting internal meetings to 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. That period accommodates people on both coasts and gives everyone mornings for focused work and the ability to schedule time for child care and other needs.

They’re also trying to break the pattern of employees believing they always need to be available. It’s particularly difficult for senior leadership to do, she said. To force it, for each week in August a quarter of the company will take a mandatory week off. When employees return, they will start four-day workweeks. On Fridays, Slack will be banned and people will take turns handling client requests.

“Most things aren’t as urgent as you think; they just happen to be in your inbox,” Ms. Shaughnessy said. “We’ll practice passing the ball entirely from person to person, as opposed to all of us being on all the time.”

One thing missing is the ability to ask quick questions across a cubicle wall, so the company set up a specific Slack channel for those. Some employees have started hanging out on video while they’re working independently, so they can bring up questions or observations as they go.

Here are five things executives and researchers said should change for remote office work to work well.

Designate time for work and nonwork

It doesn’t make sense to expect workers to be available at all hours because they’re always in their “office.” Instead, companies should reserve time for both collaborative and independent work, researchers said, and focus more on the work that gets done than on the time spent logged on. People could create rituals to mark the start and end of the workday, and companies could make clear they don’t expect messages to be answered immediately.

Judge performance, not the schedule

People have learned that they’re evaluated in part on the number of hours they spend in the office. To adapt, managers should be very clear about expectations for the work assigned and when it’s due, researchers said — then leave the “how” up to the workers and not worry about following the traditional 9-to-5 schedule.

Slash meetings